Life With Less Water: The Sobering New Normal

by Mark Dupont

“…Most westerners are unaware of prehistoric extreme climate events that complete the regions long-term climate pattern. During millennia, climate has often varied by extremes in the American West. Close examination of the evidence suggests that the benign past century and half have not prepared us adequately for what could come in the future.“

So wrote B. Lynn Ingram and Frances Malamud in the book Roam, The West Without Water, What Past Droughts, Floods and other Climatic Clues Tell Us About Tomorrow.

The current way of life in the Klamath-Trinity Region rests on the assumption that there will always be an abundant supply of fresh water. We live in Northern California after all, the land of mountains and rivers, where the water originates that that is dammed and piped to the rest of the state. Meeting water needs has been pretty simple – you stick a pipe in a creek or spring, and you get all of the water you need, all year round, for your home and garden, and maybe power as well.

This situation, however, is changing. Now entering the fourth year of drought with zero snowpack, creeks and springs that were once reliable are now precipitously low, long before the dry summer months. California has experienced extended drought before, but never after 100 years of fire suppression, with a burgeoning, semi-legal marijuana industry, salmon on the brink of extinction, and a population of 32 million people using more water, spread across the landscape in fire’s path. California’s paleoclimate records show that the entire West has experienced megadroughts many times over the millennia, so we have no way of knowing how long this drought will last. While the past reveals that droughts can be long term and recurring; future climate models indicate we may now be entering a “new normal”, where increasing temperatures mean the loss of snowpack that feeds our creeks and rivers. These changes demand a more nuanced approach to how we view and use water, but is our mindset changing as quickly as our hydrology and climate?

California’s weather is considered largely a result of conditions in the Pacific Ocean, which contains half the water on earth and covers a quarter of the globe. Two large-scale atmospheric patterns, the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) interact to determine the weather in the West. For a thorough description of these patterns (known as “teleconnections”) and how they affect our weather see Daniel Swain’s Weather West blog.

The present dry period is a result of a persistent, high-pressure, atmospheric ridge off the West Coast that has blocked moisture-bearing storms for the past four winters. Dubbed the “Ridiculously Resilient Ridge” by Swain, Atmospheric Scientist at Stanford University, this is the same pattern that forms in a normal summer, giving us months of blue skies and dry weather typical of a Mediterranean climate like the one where we live.

In most winters this system breaks up and the “storm door” opens, allowing moisture-bearing storms from the North and South Pacific to bring Fall and Winter rains to the West Coast. However, the high-pressure system has been particularly stubborn, and has persisted through many of the past several winters, as a result. Meteorologists see the formation of a strong El Niño as the best chance of breaking up the persistent high-pressure ridge and restoring more consistent rain to California.

The century starting in the late 1800s was one of the wetter periods in the West’s paleoclimate record. This also happens to have been the time when the massive water infrastructure of the West was made; dams were built, reservoirs filled, pipes and aqueduct laid, and far more water was promised than now exists.

Thus the climate that shaped early European settlement and mindset may well have been uncharacteristically moist, and it’s possible that we are now returning to dryer times.

Tree ring-sediment studies reveal recurring droughts in California’s climate history lasting from 10 to 200 years. 1987 – 1992 was the most recent dry spell, but before that an extended drought caused the Dust Bowl, one of the most dramatic disasters of the century. In the Middle Ages there were two droughts lasting over 200 years each.

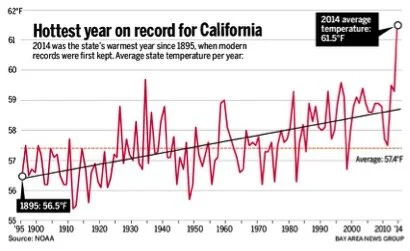

But lack of rain is not the only factor in the current drought. In fact, rain gauges in the Mid Klamath are averaging about 80% of normal rainfall this year, so why are we still in a drought? A few important factors stand out: rainfall patterns have been erratic; we are experiencing the cumulative effect of several dry years in a row; and, most importantly, temperatures are increasing dramatically. Temperatures have been climbing the last few decades, and recent years have shattered records. The year 2014 was the hottest over recorded in California by a wide margin, and the first four-month period of 2015 was even hotter.

The heat is increasing evapotranspiration, drying out vegetation earlier, extending the fire season, and, most importantly, reducing snowpack to little or none. The pattern of rainfall has also been extremely erratic, falling in bursts punctuated by long, warm, dry spells. This season, most of precipitation came from warm pineapple express storms in November and December that left no snow on the mountains and flushed quickly through the watershed, followed by unusually warm and dry weather from January through April. With this year’s rainfall levels close to normal, but little snow, it will be interesting to note how this year plays out as it may well be a sign of things to come.

Cumulative effects play a large role in droughts, and 13 of the past 15 years have been below normal precipitation. It takes a lot of rainfall to replace moisture lost in soil and groundwater, which explains why it took so long for some ephemeral streams to start flowing when the rains came last year, and many gardeners found themselves irrigating their beds this February despite a wet Fall. Meteorologists look at three-year periods of data to determine drought status, and 30-year periods to determine climate. Data from the past three years puts us squarely within drought status. (As of May we are doing slightly better than the rest of the state, but that’s not saying much.) The USDA recently changed the climate zones for the entire country to reflect the change in temperatures across North America.

This same pattern of increasing temperatures and decreasing snowpack is reflected in global climate trends. Worldwide, 2014 was the hottest year on record, and the 10 hottest years on record have all occurred since 1998. The majority of the world’s freshwater is held in snow and glaciers, and snowpack is diminishing worldwide.

A report published in 2010 by the National Center for Conservation Science and Policy synthesizes the best climate models available and projects that within 70 years the Klamath snowpack will be virtually gone.

Mark Dupont is the Director of the Mid Klamath Watershed Council (MKWC) Foodsheds Program which works to ensure that people of the Middle Klamath have access to healthy, sustainable, locally produced foods. Mark and his partner Blythe also own and operate Sandy Bar Ranch in Orleans, which accommodates guests with riverside cabin rentals and a host of permaculture practices and educational opportunities on site.