A River Lover's Guide To River Foam (It's Not All Bad)

By Charles Wickman

Yesterday, this is what I knew about the foam on this river or any river: it’s a good place to fish.

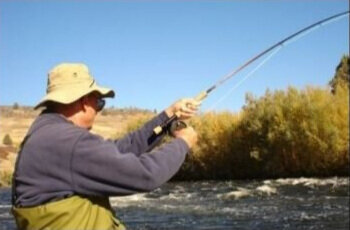

“Foam is home - Foam is home -Foam is home - E.T. - Phone - Home!” Photo courtesy Jack Trout www.jacktrout.com

Fishing Meaning From the Foam

Foam collects in eddies and along seams in the current, and collected with it are bugs, usually spent (mated and dead) aquatic insects like mayflies, stoneflies, caddis flies, midges, and drowned terrestrial insects like ants, beetles, grasshoppers, and myriad other dead and floating fish food.

If you’re fishing unfamiliar water and looking for a place to throw a fly, fishing the foam line is a solid place to start. Foam also provides cover for fish, allowing them to take advantage of slower currents under the foam mat while food rides a conveyor belt of faster current alongside them.

I grew up on a slow, warm, carp infested river in the Midwest, and bow hunting for ten pound carp, dorsal fins sticking out of billowy carpets of foam, was a favorite past time and the only reason to use a smoker. But that’s not really what I’m writing about.

What Rivers Eat

Every year, I hear people asking and concerned about the foam they see on the Klamath. They want to know if it’s toxic, something to stay away from, why don’t they see it on other local rivers, will it kill my dog? As it turns out, these are pretty good questions. And they’re probably questions I can’t answer – completely.

First, I think it’s important to understand that the presence of foam on lakes and rivers, all over the world, is almost ubiquitous. It’s naturally occurring in almost every water body and can be considered a natural byproduct of a lake or river’s “metabolism,” its digestion of organic matter in the water.

Photo courtesy of Trout Underground. www.troutunderground.com

The Klamath River, and especially the mid Klamath River, happens to have a lot of this organic matter due to its unique course (and a few impoundments and agricultural run-off), from high desert through coastal mountains to the ocean. It starts out warm and cools down as it picks up cold-running tributaries from the Red Buttes, Siskiyous, and the Marbles, as opposed to most Pacific Northwest rivers which originate in snow melt of the Cascade Range and warm as they’re herded through ranchlands and agricultural valleys to the coast. The Klamath runs warm, even hot, through its upper reaches, more akin to the carp waters of my youth, and with warmth comes eutrophication, life, death, and foam.

When (Not) To Worry

The foam you see on the river is not unlike the foam you see in your kitchen sink when washing your dishes. Or, at least, the mechanism for producing the foam is the same, if the source of ingredients differ.

Foam is born of the breakdown of water’s surface tension by surfactants, or surface acting agents, which, in turn, are born of decomposing algae, plant and animal matter which release fatty acids into the water. Surfactant molecules are interesting in that one end of the molecule attracts water while the other repels it and this bit of molecular indecision is what breaks up the water’s surface tension, allowing bubbles to form and persist when water is agitated by wind, waves, riffles or jet boats.

The trouble is, not all surfactants are naturally occurring, and here’s the rub for the Klamath. No doubt, foam on this river predates synthetic surfactants like those in modern soaps, detergents, sewage treatments, agricultural fertilizers and other things that probably shouldn’t be put in our rivers. The Karuk Tribe language has a word for Klamath River foam: chánchaaf. Interestingly, this word can also mean “white,” which seems to be a “safe” color of river and lake foam. Excessive foam, off-colored foam, or off-smelling foam can indicate something else is going on, something the Clean Water Act was meant to protect against.

Get Answers or Go Fish!

Today, here is what I’m thinking: maybe this is another utility of foam (other than cover for fish); it’s one indicator of water quality, something that can point to something else. I am not the person, at least in this post, to interpret what that something else is, but those people are around and you should pester them. And if you’re not interested in pestering people or knowing more about the connection between our water quality and our foam, at least fish it.

Charles Wickman is the director of the Mid Klamath Watershed Council (MKWC) fisheries program, working to restore high-quality fish habitat for tough but beleaguered fish runs. He is also a resident of the Middle Klamath and a lifelong fisherman.