What's The Dam Difference?

by James Peterson

The Colorado River stretches from areas of Wyoming to its terminus in the Sea of Cortez, a distance of over 1,450 miles. Hoover Dam was officially christened and open for business in 1936, approximately 30 miles south east of Las Vegas, to use the Colorado’s flow for power and to deliver significant amounts of water to the dry Southwestern United States. This was the first dam constructed along the Colorado River and at the time, was the largest man made structure in the world.

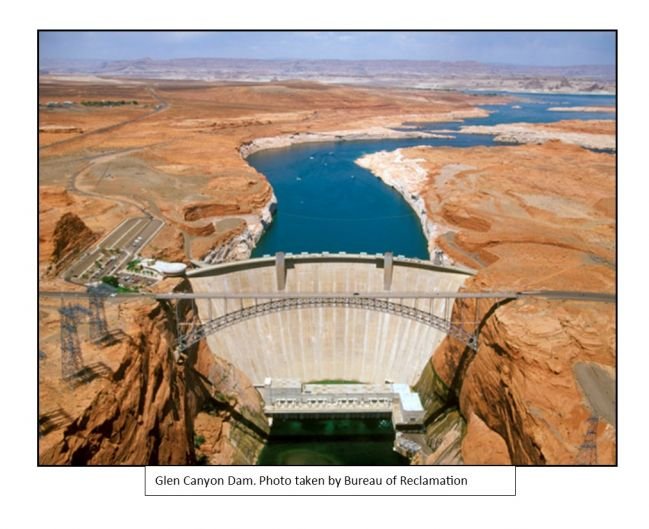

The dam stretches up over 700 feet from the river bottom and creates a reservoir that floods 110 miles of the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River. Engineering and construction of Hoover dam marked the beginning of an unprecedented dam building flurry in the United States unlike the world had ever seen before. The new government agency in charge of taming the Wests wild rivers was the Bureau of Reclamation. Hundreds of dams were built across the West along many of its mightiest rivers and each engineer seemed to want to outdo all others. Shasta Dam, Grand Coulee and Bonneville are a few names that most people living out West have heard of.

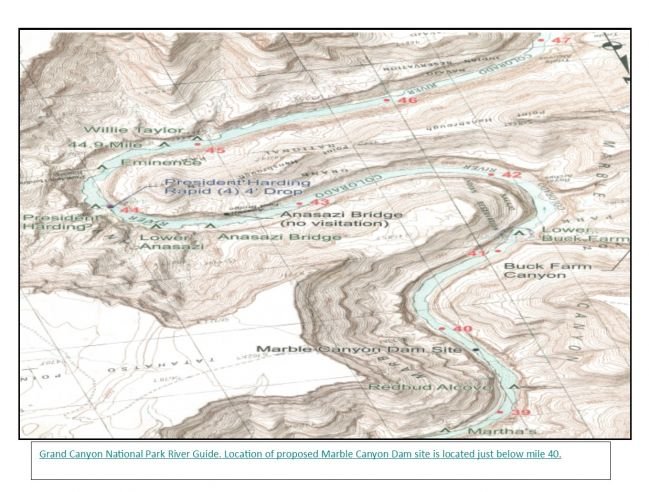

Then, in 1956, construction on the Glen Canyon Dam began. This would be the dam that brought the Colorado into total control of mankind, but, while this dam created a staggering amount of new hydroelectric power, its placement came at a steep price. The dam drowned Glen Canyon beneath a 186-mile-long reservoir. Many considered this section of the Colorado River canyon to be the Sistine Chapel of canyon country, rivaling anything within Grand Canyon National Park. The BOR and its director Floyd Dominy were also planning to build two other dams inside the heart of Grand Canyon National Park (Marble Canyon Dam and Bridge Canyon Dam) but the public outrage was so great after Glen Canyon that these projects were abandoned in order to finance the Central Arizona Project.

I recently returned from my second rafting trip through the Grand Canyon. We departed from Lee’s Ferry (just a few miles below Glen Canyon Dam) and ended inside the Lake Meade Reservoir behind Hoover Dam. The last 80 miles of this trip are spent floating the reservoir. Our guide book described the rapids and canyons that we were passing over but all we saw were flat stretches of water and large, sometimes 20-foot-tall, walls of sediment along each side of the river. During this long and slow part of the trip, I had a good amount of time to imagine the features that were now buried under millions of tons of water, and come to the realization that within my lifetime I will never be able to see what lies beneath these now calmed waters of the Colorado. I will never understand how Major Wesley Powell felt on the third month of his first exploration of the Colorado River, when his expedition encountered yet another marble canyon where the walls close in and the roar of the river overwhelms your senses.

As a whitewater kayaking and rafting enthusiast, that is what dams like the ones that have tamed the Colorado River mean to me. They represent a loss of an adventure that could change one’s life and a loss of freedom that one can only feel when out in a distant wilderness.

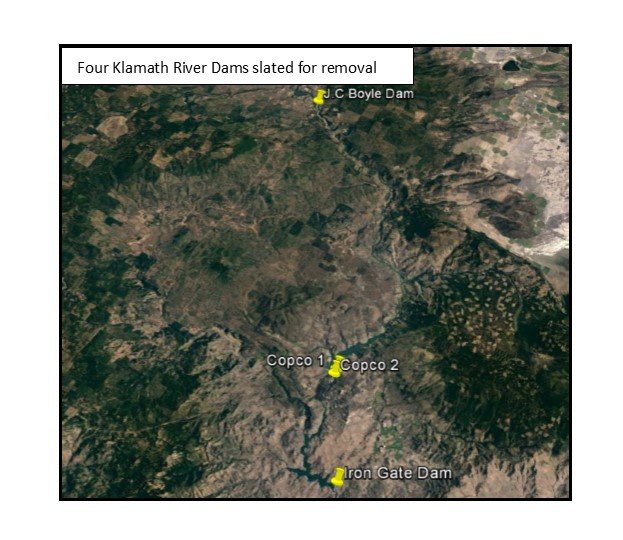

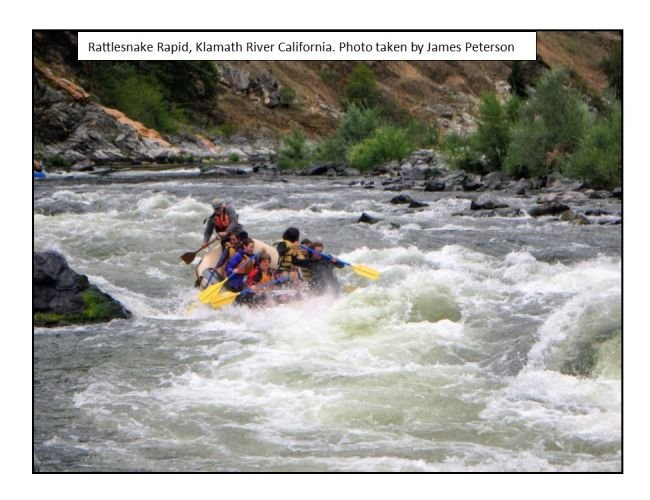

This brings me to my main point. With the Klamath Dams slated for removal beginning in 2020, an event that has been 25 years in the making could be just around the corner. If all four Klamath dams are removed, a section of river approximately 70 miles in length that has never been floated in its entirety will be opened for the first time in nearly one hundred years.

Instead of algae covered reservoirs, clean flowing water will again cascade through the landscape and a new river trip of epic proportions will be accessible to any who are willing. Outdoor enthusiasts will now be able to tie together the upper and lower Klamath in ways that have not been possible for the past century. A wealth of multi-day trips will now be available along the Upper Klamath River, and, much like when PacifiCorp removed its Condit Dam along the White Salmon River in Washington, this part of the River could become one of the most popular stretches of rafting along the West Coast.

While the Klamath River and the Colorado are vastly different river systems, they both exemplify the spirit of the wild that has drawn humans to their shores since the dawn of time, and the love of the “Great Unknown” remains the same for many who come. For “we are but pygmies, running up and down the sands or lost among the boulders," in the words of Wesley Powell.

James "Jimmy" Peterson is the Water Monitoring Coordinator at MKWC. He comes from Minnesota, and brings to the Middle Klamath a love for water and fish and a sense of stewardship for those resources that transcends borders.